Cyber Immunity isn’t just about mitigating specific cyber risks. It’s about making sure that a solution’s architecture doesn’t let cybercriminals violate security goals at all. The idea is that individual vulnerabilities aren’t so important because new exploits appear after every release anyway.

So when designing a system that’s Secure by Design, you need to take a critical look at its architecture and ask yourself a few questions. What are its vulnerabilities? What can go wrong if a component gets hacked? What needs to be changed in the architecture so that hacking one component doesn’t compromise the entire device?

A key aspect of building Cyber Immune systems is that we don’t try to analyze and protect against all existing threats and vulnerabilities. Instead, we’re governed by Murphy’s Law: Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong. We take as a given that we’ll never know all the vulnerabilities and possible attack scenarios. So we try to design the system to eliminate unsafe states altogether.

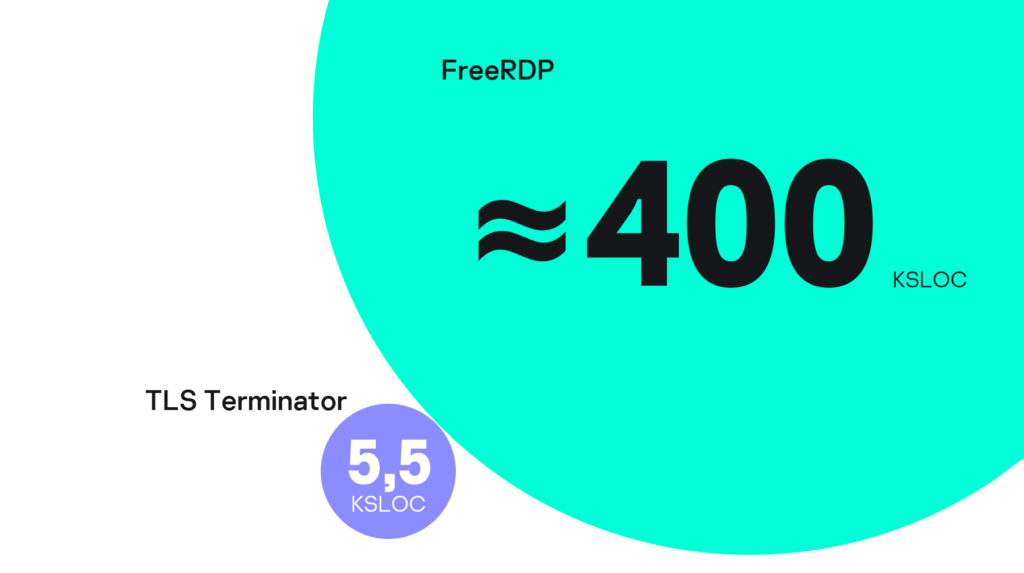

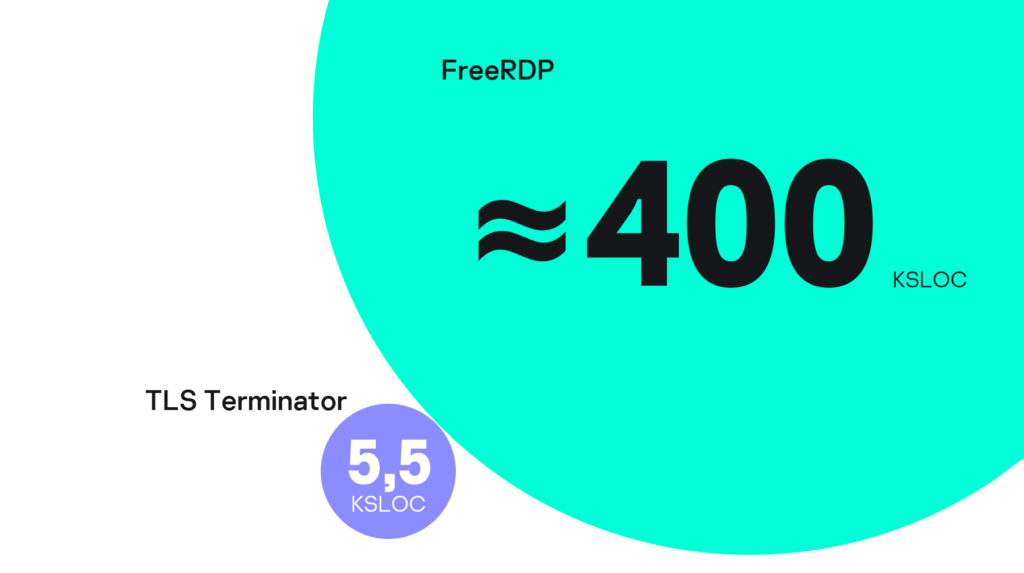

I’ll tell you about how we developed our Cyber Immune thin client (a mini-computer for interacting with virtual desktop infrastructure, etc.) using this approach. Here’s what we did to ensure that the primary security goal of the thin client was met.

In the example above, we weren’t protecting against specific vulnerabilities in the RDP client. Instead, we made it almost impossible to exploit any vulnerability and violate thin client security goals. In short, we made the device secure from known threats and exploits that don’t even exist yet.

Doing this also has another great bonus. When in the future we have a project ready and start full-fledged threat modeling, all the security gaps (or most of them) that affect security goals are already closed. This makes it much less expensive to design responses to threats.

Cyber Immunity isn’t just about mitigating specific cyber risks. It’s about making sure that a solution’s architecture doesn’t let cybercriminals violate security goals at all. The idea is that individual vulnerabilities aren’t so important because new exploits appear after every release anyway.

So when designing a system that’s Secure by Design, you need to take a critical look at its architecture and ask yourself a few questions. What are its vulnerabilities? What can go wrong if a component gets hacked? What needs to be changed in the architecture so that hacking one component doesn’t compromise the entire device?

A key aspect of building Cyber Immune systems is that we don’t try to analyze and protect against all existing threats and vulnerabilities. Instead, we’re governed by Murphy’s Law: Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong. We take as a given that we’ll never know all the vulnerabilities and possible attack scenarios. So we try to design the system to eliminate unsafe states altogether.

I’ll tell you about how we developed our Cyber Immune thin client (a mini-computer for interacting with virtual desktop infrastructure, etc.) using this approach. Here’s what we did to ensure that the primary security goal of the thin client was met.

In the example above, we weren’t protecting against specific vulnerabilities in the RDP client. Instead, we made it almost impossible to exploit any vulnerability and violate thin client security goals. In short, we made the device secure from known threats and exploits that don’t even exist yet.

Doing this also has another great bonus. When in the future we have a project ready and start full-fledged threat modeling, all the security gaps (or most of them) that affect security goals are already closed. This makes it much less expensive to design responses to threats.